If a person with a gun attacks you from a distance, then the only defensive weapon that makes sense would be a gun (or other projectile weapons). However, if the attacker is physically close to you, you have more options, and one option to consider is a knife.

Compared to a gun, it is relatively small (or at least less inconveniently shaped) and light, making it less obnoxious to carry, and easier to conceal.

Plus, it would generally be less restricted by laws, completely silent, less expensive, and not subject to a limited ammunition supply.

You need to maintain personal distance from potential attackers and be prepared with bare-hand techniques at least until you can disengage long enough to safely draw your own knife (or other weapon).

This requires situational awareness and some martial arts training. In particular, it requires plenty of “sparring”, practice with a partner.

You can start with knife training, but you will still have to learn about stances, balance, blocking, and targets, so it would tend to be more efficient to start with martial arts and then add knife training.

What style, you say? That depends on what is available locally, and what “feels right” to you. I’d check out several options, and even take a trial lesson in any which appeals. If the place offers knife training, that would be a significant incentive.

Doing a quick search of knife training currently local to me, I found FMA is available, as well as Aikido (related to jujutsu), and a Krav Maga school that specifically includes knives.

Table of Contents

Knife Anatomy

A knife is simple in concept, but there is more to it than you may think. Refer to the image above to get an idea of what parts make up a knife:

- The HANDLE is the part you hold onto

- The TIP is important for stabbing

- The EDGE is used for chopping and cutting.

- The BELLY is used for slashing.

- The BACK EDGE may be partially or fully sharpened, or not sharpened at all. If not sharpened, it may be used for blocking in some styles.

- The SPINE is the thickest part of the blade. It may be down the centerline of the blade or identical to the BACK EDGE.

- The GUARD (aka HILT) helps prevent your hand from slipping over the EDGE. It can also be used to block or catch an enemy’s blade in some styles. A “full” guard provides more protection but limits some of the ways you can hold the knife, so often there is only a “half” guard.

- The BUTT or POMMEL, if it extends beyond the hand, can be used as a blunt striking point. BUTT is the general term; POMMEL usually refers to a discrete part that is often decorative or functional.

Knife Choices

A misconception is the idea that “any knife will do”. With a knife, your options are to slash, cut or stab, or possibly chop.

Different styles of fighting will use and even hold the knife differently, and a particular style of knife will fit those techniques the best.

Thus find your training first, and then select from the knives or knife styles they recommend.

And first thing, get a training knife as close to your real knife as practical. After all, you are going to have to do a lot of sparring and we want to keep training injuries to a minimum.

When choosing a knife, there are some basics:

- ✅ It has to be strong. Having the knife break on you while using it is really bad news. The two weakest areas can be the tip or the junction between blade and handle. Having the blade break elsewhere is less likely unless you get a piece of junk with low quality, poorly treated steel or a poor design.

- ✅ You must be able to get the knife into service quickly and reliably.

- ✅ The knife must be SHARP. The duller it is, the less effective it will be. Every time you use your knife, it will reduce its sharpness. If you use your fighting knife for any purpose, resharpen it as soon as possible. Make sure you have the equipment and skills to return it to razor sharpness.

These elements are pretty much independent of the style of use. The first one favors a full tang fixed blade knife. A folding knife is inherently weak at the junction between blade and handle because that point is DESIGNED to move.

You have relatively loose-fitting, small parts, which makes this point much more likely to break than a solid slab of steel.

But if concealment requirements make a folding knife the only choice practical to you, then choose one with a very strong lock, which not only reduces the chance of the joint breaking, but the chances of the blade folding up on your fingers during use.

Usually “liner” locks are very common and quite strong. Cold Steel’s “Tri-Ad” lock seems to be one of the “strongest” non-liner lock styles.

I prefer the “Axis” lock from Benchmade or the similar “Ball Bearing” lock from Spyderco. They are easier to close with one hand, and are fully ambidextrous. My second-place favorite is the liner lock, which is rather less ambidextrous.

“Switchblades” (including OTF – Out The Front) and “assisted opening” knives may look impressive in action, but they are less satisfactory than manually opened knives.

This is because they have more parts to break, the joints have to be looser in order to function reliably, and they are not that reliable at opening.

Dirt in the mechanism (hey, it’s a pocketknife) or the blade running into something while opening can prevent them from locking open, and that could have serious consequences.

Even if you realize it is not locked open, manually locking it will probably not be a practiced maneuver, and will likely require time and attention you may not have.

Moreover, some places have more stringent laws about switchblades than they do for “manual” knives.

The second criterion again favors a fixed-blade knife, in a sheath that does not have straps, snaps or flaps. No matter how you carry the knife, whether it is fixed blade or folding, you must practice drawing it, and practice some more.

The goal is to produce it quickly and smoothly, preferably in one continuous motion, every time. However the knife is carried, it must be secure until you need it. If it falls out of the sheath or your pocket, it could be embarrassing at best and fatal at worse.

As for sharpness, this requires much research. The maximum sharpness is dependent on the cross-section design of the blade and the molecular structure of the steel used.

As a hint, usually, but not always, knives made from better steel formulations tend to be more expensive. Once you have a blade as sharp as possible, edge retention (how long it holds that sharpness) is based on the steel formula and heat treatments.

Knife steels range from “carbon” steel to “stainless” steel. Carbon steels tend to be capable of a sharper edge, tougher, and easier to sharpen, but rust if you look at them wrong.

Stainless steels don’t rust as easily, but often are a bit more brittle and harder to sharpen.

The steel used for your knife is pretty important, but the treatments applied by the manufacturer usually make the difference. Worse, today’s best steel is often tomorrow’s second-rate choice.

Other basics are highly dependent on HOW the knife will be used and probably should not be chosen until you have chosen your style.

You COULD get the knife you like and then attempt to find training in how to use it, but this has a high probability of ending in failure. And failure could mean death or severe injury, so should be avoided to the degree possible.

It has to be long enough to support the techniques you will be using. If you will be attempting to stab vital organs, then you will need at LEAST four inches of blade, and five or even six inches would be better.

Blades for slashing only and/or shallow stabbing can be shorter. Chopping blades can and probably should be longer.

- It has to be an appropriate weight. Too light and it won’t have the oomph to cut deep, while too heavy and it will be unwieldy.

- The blade shape needs to be appropriate for the techniques you will be using.

- The fighting style you use will have a particular way of holding the knife (there are four ways I find suitable for various forms of combat, and other ways of holding which some obscure style might be able to make effective).

The handle size, shape, and material must support the hold(s) you will be using, and allow the hold to be comfortable and secure. This means that it must be unlikely the knife can slip out of your hand.

In addition, your hand must not slip forward onto the blade, even if your hand or the knife is wet or oily. You lose points if you cut yourself with your own knife.

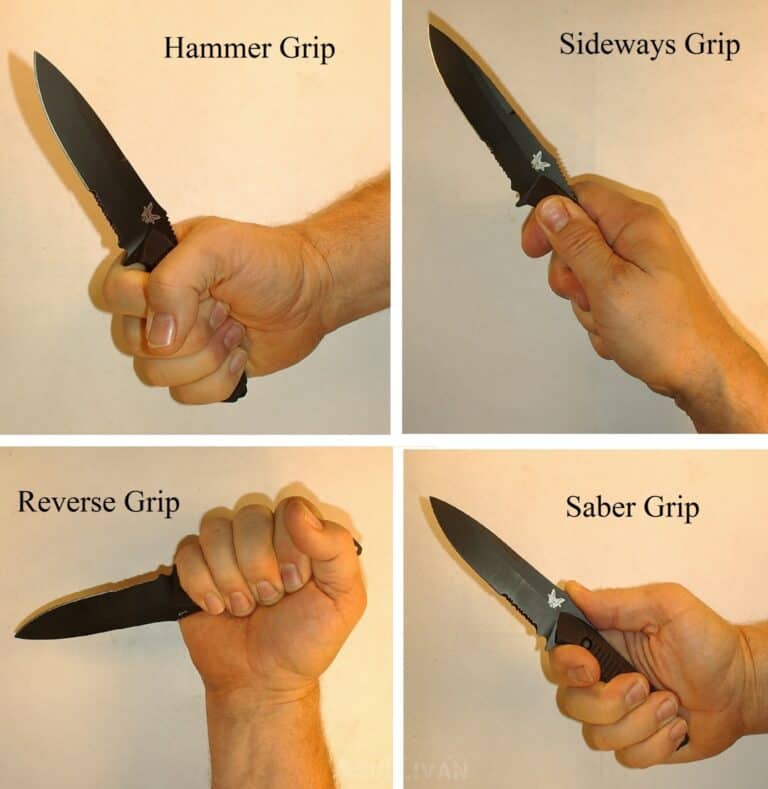

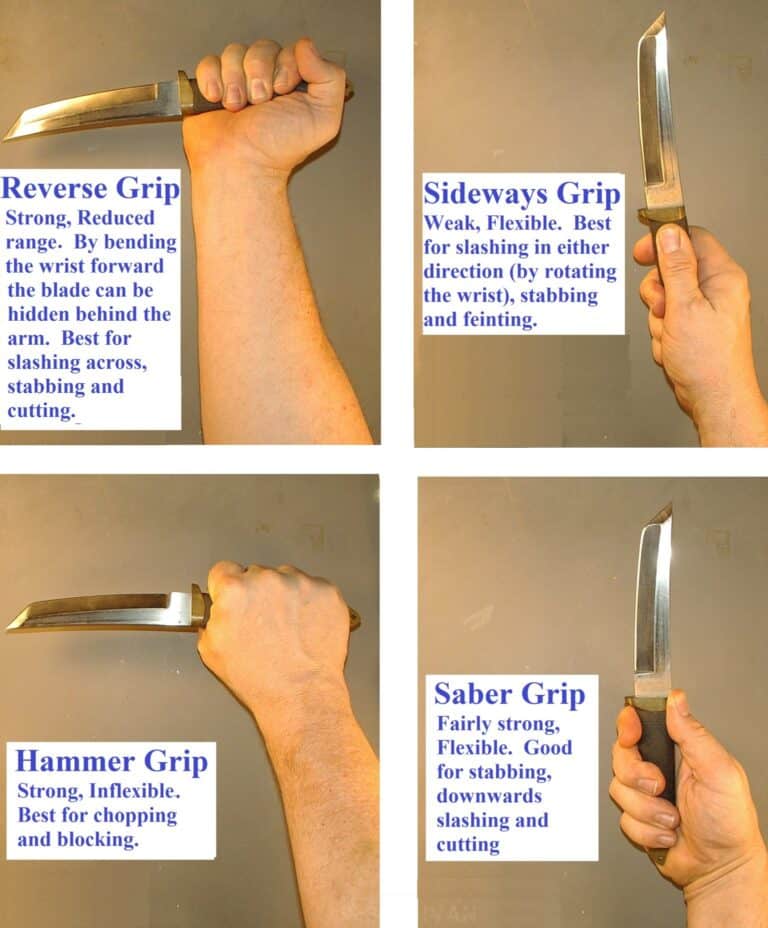

Holding the Knife

When it comes to defending yourself with a knife, there are a variety of grips you can use. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages, so it’s important to know which grip will work best in any given situation.

Below we will discuss four different knife grips: the hammer grip, icepick grip, saber grip, and quarter-saber grip.

We’ll go over the pros and cons of each one, so you can make an informed decision about which defense technique is right for you.

Hammer Grip

The hammer grip, or forward grip, is perhaps the most common grip used in self-defense applications.

It’s simple and straightforward: you simply hold the knife in your hand, thumb curled into a fist, with the point facing up and the blade facing away from you. This grip gets its colloquial name because you hold your knife like you would a hammer.

This grip is easy to learn and execute since it is inherently understood, as many tools are designed to be gripped in this way.

The hammer grip technique gives you a good amount of control over the blade, and is extremely strong, producing the greatest force possible in terms of controlling the knife.

In terms of usage, the hammer grip is a straightforward and adaptable technique.

Range is maximized and hacking, thrusting and blocking are all easily accomplished, and significant power can be generated for stabbing although the orientation of the knife means that such stabs are likely to be low line in origin.

However, it can be difficult to generate a lot of power for downward stabs with this grip, so if your knife is oriented for stabbing the hammer grip might not be ideal.

Nonetheless, the hammer grip is extremely well-rounded, excellent on defense, and is a highly intuitive, secure grip, meaning it is perfect for most self-defense applications and is likely to be the first grip that a beginner learns.

Icepick Grip

The icepick grip, or reverse, grip is identical to the hammer grip except that you hold the knife upside down, with the point down and blade facing out.

Certain variations of the technique have the blade facing inward. Once upon a time, this technique was seen as a flashy or frilly martial arts-oriented variation, although the orientation of the knife in this way displays obvious stabbing intent.

Many gangland knife attacks and professional assassinations are carried out with a knife held in this way.

This grip gives you more leverage at the cost of range and allows you to generate dramatic power with your strikes.

It is reasonably effective on defense, particularly close in, and enables users to deliver ferocious, deeply penetrating stabs as fast as they can retract the knife and reinsert it.

Rapid fire stabs of this type are commonly referred to as a “sewing machine” or “stitching” attack

Like the hammer grip, the ice pick grip is an extremely strong hold, and affords the wielder maximum strength and control over the knife.

However, it can be difficult to control the blade in this grip when you want to employ slashing or hacking techniques, and thrusts will be clumsy with greatly reduced range.

Also, users must take care that a blow to the top of the arm or hand does not drive the point of the knife down into their own bodies, so you have to be careful on the defense.

Saber Grip

The saber grip is a more advanced technique that gives you considerable additional power and control over the blade when slashing or chopping.

To execute this grip, you hold the knife in your hand as you would with the hammer grip, only you will have your thumb extended directly along the spine or top of the knife.

Adherents claim this gives considerably more finesse and control over the orientation of the edge, allowing greater accuracy, while also affording better leverage when chopping or cutting.

A regular fixture in Filipino martial arts, the saber grip allows you to deliver powerful strikes while still maintaining a good amount of control over the knife, although compromising the grip by not curling the thumb over does weaken the hold somewhat.

The saber grip is ideal for those who prefer the advantages of a point up, edge out hold while maximizing versatility for chopping, cutting, and thrusting.

The primary disadvantage of the saber grip is the weakening of the hold, as mentioned, but also the vulnerability of the thumb to damage.

The hand is always a high percentage target in a fight, and the thumb, crucial for control, will be even more vulnerable when holding the knife in this way.

Quarter Saber

The quarter-saber or “sideways” grip is similar to the saber grip, except that you hold the knife with the handle rotated a quarter turn so the thumb is along the side of the blade, edge facing toward the centerline of the body.

The quarter saber grip offers a variation on the advantages gained by using the standard saver grip, namely that slashes and quick counter-attacks can be enhanced by a sort of whipping motion or flicking of the wrist.

This can allow even a short blade to slash deeply into a target. It is also reasonably effective when thrusting.

Unfortunately, these advantages come with a lengthy list of disadvantages, namely the fact that hacking and shopping performance is compromised due to the orientation of the blade compared to the arrangement of the bones in the arm, and the fact that the grip is often quite weak in comparison to others discussed above.

Any knife that does not have a symmetrical handle or one that is ergonomically designed for gripping this way is likely to be uncomfortable and will sacrifice maximum surface area contact.

In short, the quarter saber grip, although traditional and still taught fairly commonly in systematized knife-oriented martial arts, is one that should be used sparingly if at all, with the exception being a knife designed to be held accordingly.

Which Grip Method is Best?

Whatever type of grip you decide to rely on when using your knife, make sure you assess it in context with the knife, or knives, that you will actually carry.

Intrinsic factors concerning the knife handle, like shape, finger grooves, choils, texturing, symmetry, and more will all impact the comfort and security of a given grip.

Some knives are purpose-designed to be held with a certain grip, and other grips could prove to be marginal or even dangerously faulty.

Other knives might sacrifice maximal performance and one orientation to allow a user to apply whatever hold they wish, reasonably effectively, with any grip detailed above.

In short, there generally is no “best” or “only” way to hold your knife, and conversely, there are very few methods that are truly terrible.

Your grip should always facilitate use of the knife for its intended purpose; in a self-defense scenario strength, rigidity and security are concerns of utmost importance. Train accordingly.

Considerations for Defensive Knife Users

There are quite a few other things to consider in the context of knife-based self-defense.

First and foremost, whatever you might think about knives as compared to guns, in the eyes of the law a knife is always, always a deadly weapon, and even brandishing it is considered deadly force in most circumstances.

Accordingly, you should never draw your knife in order to win an argument, scare someone off, or for any other purpose unless you are in a legitimate self-defense scenario.

And because you are resorting to a lethal weapon and preparing to use deadly force of your own in defense you had better be able to articulate a reasonable belief that you yourself, or someone else, could suffer great bodily harm or death at the hands of your attackers.

Also, keep in mind that any self-defense encounter you get involved in where you rely on your knife is probably not going to be taking place in a world without the rule of law.

There’s going to be an aftermath, and that aftermath will take place in a courtroom. Once there, though alive, your choice of weapon might well work against you.

Although we are all supposed to be afforded the same strict protections under the letter of the law, the reality is very different.

Prosecutors, judges, and juries have their own biases, biases that might well prove detrimental to your case and cause. In short, the knife is seen ultimately as something of a “bad guy” weapon.

The wounds that a knife inflicts even in the hands of an untrained user are the very stuff of nightmares.

How might a prosecutor spin the appearance of such injuries to a jury? Are such wounds the result of the minimum needed amount of force, even lethal force, to stop the unlawful attack?

Or were they the frenzied assault of a person who was enraged at the advance of the poor, misunderstood soul sitting opposite you? How is that going to make you look?

Never mind that you tried to get away from the four-time repeat felon and attempted murderer who was intent on mugging you before you pulled your knife on him in a desperate bid to save your own life: The fact that he is cut to ribbons and swaddled like a mummy sitting there in the courtroom will reflect very poorly on you.

Yes, guns are deadlier pound-for-pound. Yes, the wounds that a bullet leaves in its wake are just as terrible, at least on the inside.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t really matter once you’re out of the self-defense situation proper and in the courtroom. Optics do matter. Perception matters, and often counts for more than it should.

Self-defense trainers with a focus on edged weapons have taken to training students around these realities by emphasizing the fact that the wounds, or force, delivered by a knife can be modulated.

These trainers assert that a knife wielder, a skilled wielder, could deliver non-lethal or less-lethal cuts to strategic parts of the attacker’s body, particularly the top of the arms, back of the hand, and so forth in an effort to stop the attack without resorting to overtly lethal strikes.

This, in my opinion, is foolhardy. Because a knife is always, always categorized as a lethal weapon any such injuries inflicted by it always constitute the willful use of lethal force.

The proposed defense against such is the edged weapon equivalent of a firearm user saying they only tried to shoot the bad guy in the arm or the leg. Only a layman or an idiot would believe that such a wound had no possibility of being lethal.

Whether a small cut or shallow poke with a knife is, in fact, non-lethal and was delivered skillfully is irrelevant: the precedent, legally, is already well entrenched.

If you are forced to defend yourself with a knife, no matter how plainly justified you are, you can depend on your legal battle being made much more difficult in the aftermath.

Knife Examples

Although we are not choosing a knife at this point in time, here are some examples of possible styles. For instance, one of the stranger knives is the karambit:

It is primarily for slashing. On the other hand, we have the “dagger”, which is sharpened on both edges, excels at stabbing, and is decent at cutting, but poor at slashing.

Disclosure: This post has links to 3rd party websites, so I may get a commission if you buy through those links. Survival Sullivan is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. See my full disclosure for more.

There is a handle style called “subhilt fighter”, which has a second “guard” which helps lock the knife into your hand. The blade style of this model is “drop point”, which is one of the more versatile blade styles, and is good at stabbing and cutting, and decent at slashing.

The “bowie knife” is a classic, for styles that can use the size and weight, which is a particular advantage when chopping. The blade style is “clip point” which increases the sharpness of the tip but makes it weaker.

Some bowie knives have a very deep clip, which gives a needle tip with no strength at all. If the clip is sharpened, it enhances the slashing ability, as you can slash both forward and reverse, but it weakens the tip even more.

Another classic is the K-Bar Marine Combat knife (training version). It is decent for stabbing and good at slashing and cutting. This blade also has a clip point.

My favorite is the Cold Steel “Tanto”, based on the shortest of the three-blade set typical of the samurai warriors. It is good at stabbing, slashing, and cutting.

According to their website, Cold Steel (who popularized this style when starting their company) does not seem to make it anymore, except in the insanely expensive “Master” and “Magnum” versions and the “Lite” model which appears to have a plastic guard and pommel.

Much of the time, it is impractical to have a fixed-blade knife with me. For EDC, I like the Spyderco Manix 2 XL. It has a handle that is excellent for my style and a blade shape that is good for stabbing and cutting, and decent for slashing.

The large hole in the blade is about the quickest opening system I’ve found. In addition, it is well designed for everyday use and most survival tasks.

At nearly four inches blade length, it is not petite; there are similar, smaller Spyderco models that would be suitable for last-ditch defense, but avoid the “lightweight” models. They don’t have steel liners, which means they are not as strong.

Techniques

Giving specific techniques probably won’t do you much good; you need actual training and practice to be effective. Techniques that work for my style and knife might conflict with yours.

However, there are some general hints that might be of more universal use. Keep in mind your primary goal, which is to survive the fight with minimal damage by avoiding the fight, or ending it as quickly as possible.

In order to provide the greatest chance of doing this, always strive to maintain your distance, ideally at the limit of the attacker’s range without him moving his feet. The closer the attacker is to you, the harder it will be to defend against him.

Backing up may be necessary if he advances, but this will eventually get you in trouble. It is better to evade to the side some of the time, but don’t be predictable.

Of course, the opposite is also true; the closer you are to him, the harder it will be for him to defend against you. The one doing the closing, with a strategy, has the advantage. If any closing occurs, let it be deliberately by you, with a plan, rather than by your opponent.

The next concept, particularly of concern when you are using open hand defenses, is to avoid focusing completely on the knife.

The attacker has another hand and two feet and other body parts that can do you damage, and if both your hands or all your attention are occupied with the knife hand, your ability to block any other attack is lessened.

The converse is also true. If you have an opening for a kick or strike other than with your knife, take it. Just be confident he can’t get to your leg or arm with his knife.

One thing I was taught, which may not be included in some styles, is if someone executes a knife technique against you, attack the knife (more accurately, the hand holding the knife) rather than the person.

As the attack technique is executed, the knife hand is closer to you than the attacker’s body, which gives you the reach and timing advantage.

If you damage or disable the knife hand, usually by cutting across the wrist, then the knife threat may be removed or at least reduced. As an aside, this should indicate to you the advantages of also training using the knife in your “weak” hand.

All techniques will involve moving your knife from where it happens to be, to a position and orientation that should have an effect or at least gives that impression (feinting).

Whenever practical, try to include a secondary technique as part of your recovery or use the ending position of your primary technique as the starting position for a secondary technique.

For instance, after a slash in one direction, stab or slash in the reverse direction. Don’t focus on single techniques, since your opponent then only has to bother with single counters.

Targets

In order to end a knife fight as quickly as practical, with minimal damage to yourself, consider what will stop the fight. Pain might do it for some attackers; most people do not like to be cut and that may be enough to dissuade them.

However, don’t rely on this; some people are willing to take the pain, and some are so charged with adrenaline (or other drugs) they won’t “feel” the pain until later.

More reliable would be if the attacker can’t breathe, does not have enough blood left to circulate oxygen, or does not have working blood circulation organs. Finally, if he is paralyzed or can’t stand up or move or see, you can easily get away.

Thus, you need to know the targets on your opponent to know where to strike for best effect. For that matter, you will also know where to defend yourself the most.

Some of these would be difficult to access during a fight. The back of the neck and back of the knee would seem to be unavailable in many cases. You would need to be familiar with rib placement and have a good degree of accuracy to be sure of getting through the rib cage to heart, lungs, or liver.

That makes throat, shoulder, and groin the most practical of these targets. To blind an attacker, you can attack the eyes or slash above the eyes to get them filled with blood.

The wrist is often accessible, and although a cut across might not put him out of the fight right away, it may disable or reduce the effectiveness of the hand.

Below the rib cage (abdomen) is fairly accessible, and if you stab upwards under the rib cage and damage the diaphragm, it should affect the attacker’s breathing.

A kick to the knee can cut their mobility significantly. Finally, if you find yourself on the ground or have a kicking foot near you, slicing the Achilles tendon will also limit the person’s mobility.

If you don’t have an effective target, go for an ineffective one. Any damage you inflict can add up. If you complete a stab, remove the knife as quickly as possible, since at that moment, you are essentially “disarmed”.

In addition, the blade will somewhat block blood loss, and that is contrary to your goal. Twisting the blade as you remove it can increase blood loss.

Ready to Fight?

Forget about what you see in knife fights on the screen. They are choreographed to be visually pleasing and to result in the desired conclusion. In the real world, knife fighting is an attempt to avoid death or severe damage.

The most effective way to get good at it is to survive several such fights, which is a path with very high odds of failure.

A less dangerous path to have a decent chance of surviving a knife fight is lots of the remotely second best method of gaining competence, which is training and practice, practice, practice. When you can win all your practice fights, your odds of winning a real one are increased.

What style of knife fighting or martial arts do you think is the most effective?

While employed at a major computer firm, I took advantage of a number of club activities and classes offered to employees, including martial arts, advanced first aid, rock climbing and wilderness survival. It is my nature to “tinker” and delve into the technical side of things. As a kid riding bicycles, I learned bicycle mechanics. Knife collecting led to throwing and making them, as well as leatherwork for sheaths. The martial arts led to knife fighting and making and using primitive weapons.

I have carried a number knives over the years from folders to fixed blades. (Buck, kirshaw, Spyderco, kbars, randals and glocks). I was the victim of a knifing as a child living in a low incoming complex. My brothers rival walked up behind me “aren’t you xxx brother?” as I turned around I heard the switch blade open, he took a single slash across my midsection, as I pulled back he got my arm and the back of left hand. I was 9 years old, he was 14 or 15 years old, anyway I can remember clear as day and I am 58 years old. I trained my daughters knife fighting because you never know, they are 31 and 32 years old. Skills are like an onion with many layers, H2H open hand, street weapons, knives are redant skills for that one momment your in grappling range or as some say, fighting in a phone booth, which I doubt a millinial has ever seen. Just my 2 cents folks from experience (58 years livin, 10 years DOD, 3 years security, 3 years contractor central america